Bell Ringing

Ian Douglass reviews Jenkin van Zyl 'Dance of the Sleepwalkers' at Edel Assanti (19 January - 9 March)

The walls are painted grey, the floor has been carpeted with screen-static pixels of grey, and, outside a window, a view onto another grey London street, with a door promising escape. But the door is locked, the city sounds are suddenly muffled by the carpet. Is this purgatory?

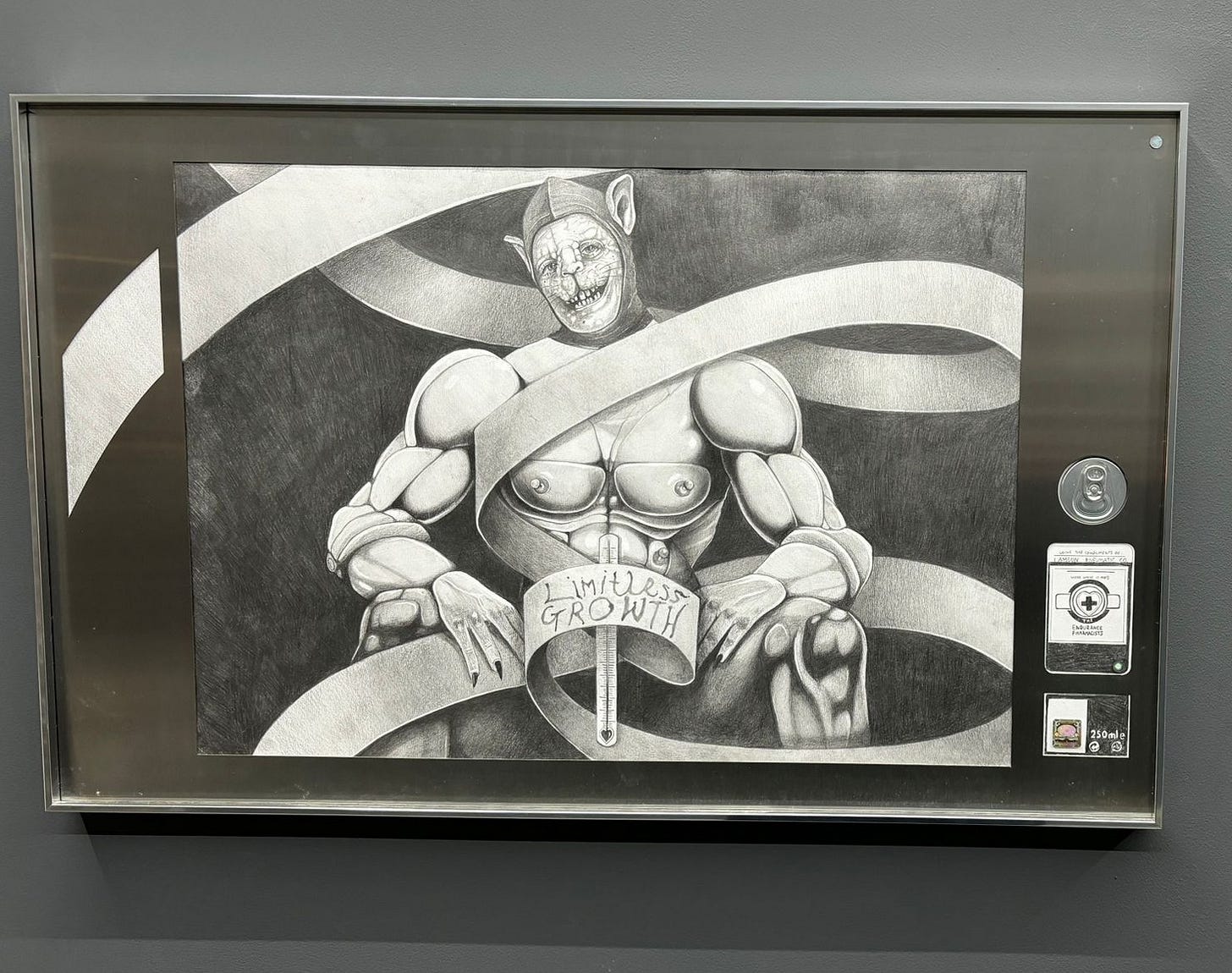

A rectangular light above creates its own geometric halo in the space, making the cold contours of the room feel as sharp as the slit steel on display. Various rat-bros in the drawings are athletic, ecstatic, mockingly jeering and flaunting their clear-cut self-important superiority. I can almost hear their voices taunting me with an impish inflection (they’re definitely on steroids).

The anti-heroes don fetishistic stockings, draped in domineering bondage gear, pseudo athletica garb, while hanging off one another. These characters immediately invoke Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle and its ritualistic, grotesque offerings of gargantuan masculinity and membrane, brought into sharp 21st century high definition. Promises emerge of puritanical biohacking, the demented dream of modernity and perfection putrefied into archetypal antagonism.

Sleek stainless steel further solidifies the smoked silvery overtones of the graphite drawings and space. There is a sense of the clinical, the technological, and further hallmarks of sports competition: trophies are drawn and alluded to, with one work reading ‘no happier place than a loser’s’. But van Zyl bypasses simple readings, with military dog tags and the top of a can of soda emerging from one steel frame.

At the same time, the cartoonish aspect of the rat-humanoids reduces their threat, unlike the rest of the space, rife with a certain corporatized menace. Buzzer buttons occupy space next to some of the drawings, with diverse and tantalising labels such as 'Unnatural Occurrences and/or Unexplained Lights', 'Full-Frontal Pornography', 'Farewells' or simply 'weather', 'me', and 'you'. This interactive element of pressable buttons steals the show, embracing the tactility of the metallic with all of its super-smooth sensuality, while breaking the ‘look but don’t touch’ boundary of London gallery shows.

But none of the buttons work. The exhibition text refers to neoliberal policies, subcultures and notions of inclusion within social spheres. In this space, you can almost feel late capitalism made potent and permanent. Suddenly, the rat-humanoids are downtrodden victims trying to ascend out of a vicious cycle, traumatised and dehumanised like war veterans, their bodies nothing more than strategic objects, scientific data substance, experimented on by some grand wizard that is nowhere to be seen, yet felt everywhere, always watching and orchestrating with phantom palm and eye.

The exhibition feels simultaneously minimalist and maximalist. Its restrained colour palette of wan and alternating grey hues, whether stainless steel, graphite, or the walls and floor are of a suppressive subtlety. And yet, the show feels maximalist in supplementing a narrative background that viewers sense on the back of their neck or tip of their nerves, a hidden excess of van Zyl’s fabricated psychosphere that we can witness without access. A whole world at our fingertips, yet still far beyond our reach. That rings a bell.