A strange creature, a cross between a life-sized human and a gigantic hare, sits in stiff-backed meditation on a stage on the ground floor of White Cube, Mason’s Yard. Its huge ears reach almost to the ceiling. It has the presence of something alive: the rabbit mouth is slightly open, the arms relaxed, the eyes looking intently forwards, though with a sense of brooding, no Buddhist enlightenment. Before it is a small hole into which, with all due apologies, we must now plunge, down, down, down into the uncanny valley, Wonderland, the White Cube basement, etc., where twenty-five more of Altmejd’s sculptures are waiting.

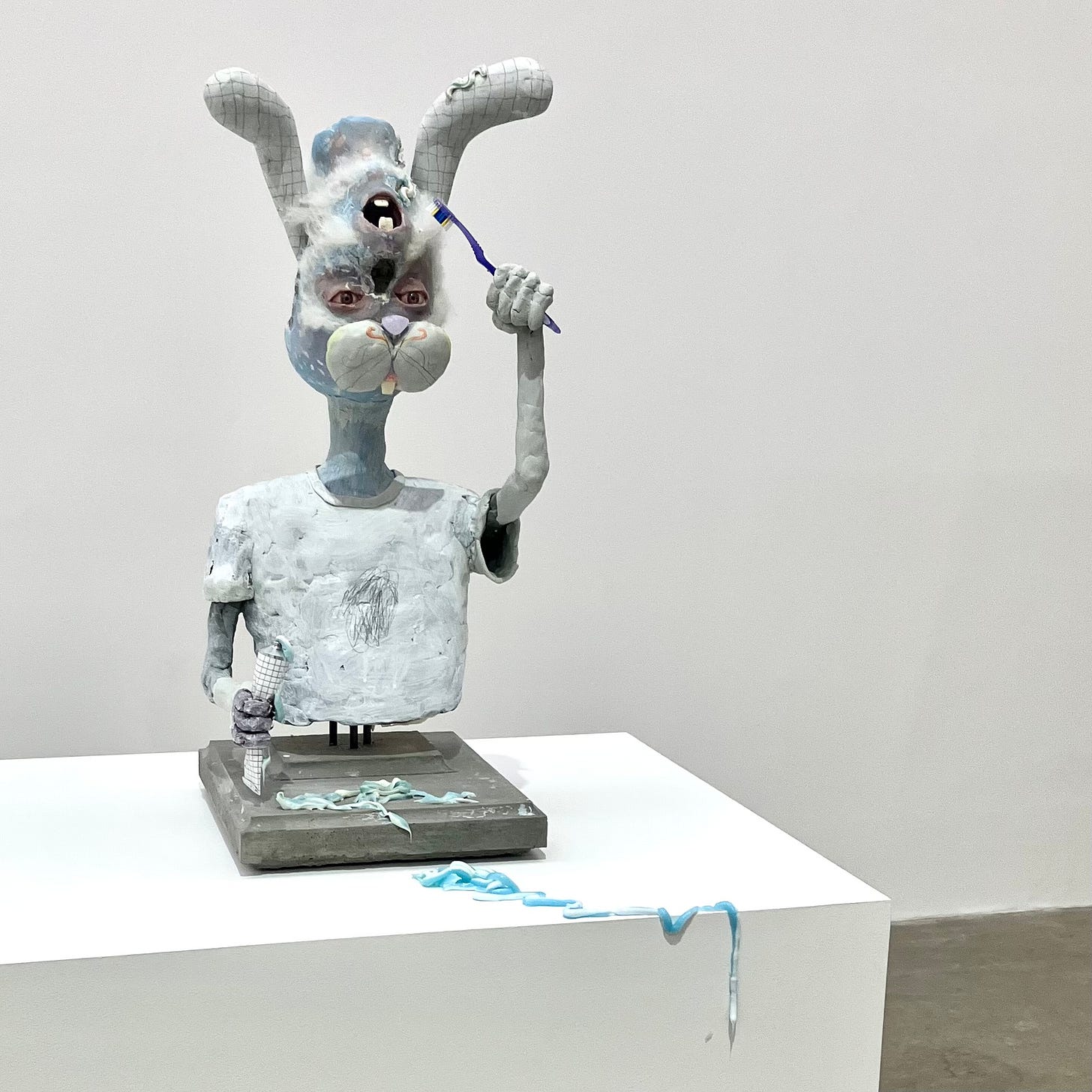

Despite being a collection mostly of busts, the works achieve the effect of having been running around only moments before our arrival. One, Glitch, holds a tube of toothpaste, which gloops over its plinth, the floor and the walls as if the bloodshot-eyed, double-mouthed rabbit-child has been chucking it about. Here, as in the rest of the sculptures, elements of the human form have been spliced, diced, distorted and reconfigured with animal forms and crystals, producing a cast of monsters from a circle of hell as deep as any painted by Hieronymus Bosch.

Altmejd employs the surrealist technique of doubling. Twin Flame, for example, seems to be two identical bodies merged into one, slightly out of alignment: a doubled hand holds up a doubled lighter, ignited, with doubled bunny ears on the figure's head, three eyes above a doubled nose and doubled bunny front teeth. This artwork operates on the part of the brain that recognises human faces, producing a kind of prolonged double-take in the viewer: visual mischief that is apt for a show based on the Trickster, a mythological and literary archetype who appears widely across cultures under names such as Hermes, Brer Rabbit and Puck.

The sculptures divert from conventional ideas of the Trickster in one key respect: their monstrosity. The Mother, for example, is a purplish human bust with an inverted head spliced onto it, the ears embedded into the skull, a blank, lost expression in its eyes and mouth, topped with an open slice of neck. In an otherwise impeccable show – cohesive, ingeniously curated, imaginative – the sheer grimness of the sculptures becomes monotonous and saps it of warmth, a quality that, for all his pranks, Puck never lacks.

The Mother, 2022

There is a playful element to Altmejd’s sculptures, but it is a mad scientist’s kind of play, a willingness to treat the human body as nothing but flesh, abject and infinitely experimentable-upon. The show offers no respite from it, and ends up repulsing more than it attracts. If Wonderland is the high, David Altmejd is the comedown. Even Bosch painted heaven sometimes. It is a relief to climb the stairs and step back outside.