In Rear View a narrative is distributed amongst several car accessories displayed in a former railway-arch garage, now community library (though soon to be reclaimed for a process erroneously termed ‘development’). The artist’s mother, a used car dealer, gave her daughter a car for her birthday. The artist, Eleni Papazoglou, took her mother out for a drive – and crashed.

The space is loosely associated with a car interior. On the floor, maps printed onto car mats point to where the accident happened. A video on a smartphone – displayed on the window via a car mount – records her mother’s pleasure in giving the gift. A car key is plugged into the wall, with a bulky keyring that includes a plastic-mounted photograph of a hand holding the keys in front of the new car. Yet in the centre of the book-lined gallery there is, slowly rotating on a circular plinth . . . a huge white fridge.

(Where we crashed, 2023)

Why a fridge? Untitled [No one ever shows you off] is covered in a few magnets that show more pictures of the interior of the car, and some high-visibility stickers of the kind put on ambulances. These seem to allude to emergency responses to road traffic accidents. Stuck on the fridge, they signal that it too is a life-saving machine, which anyone getting home at the end of a long day knows well.

This container is substituted for the show’s absent car as an embodiment of a mother’s love. Car becomes care. Not to sound mesolithic but even today a mother’s love is very often expressed via the contents of a fridge. The slowly rotating plinth on which this support-giving, food-providing monolith is mounted suggests a degree of admiration, even idolisation. It is a striking and affectionate (if not exactly flattering) tribute to a person who appears to combine the role of domestic caregiver – traditionally given to women – with the more typically male work of a used car dealer.

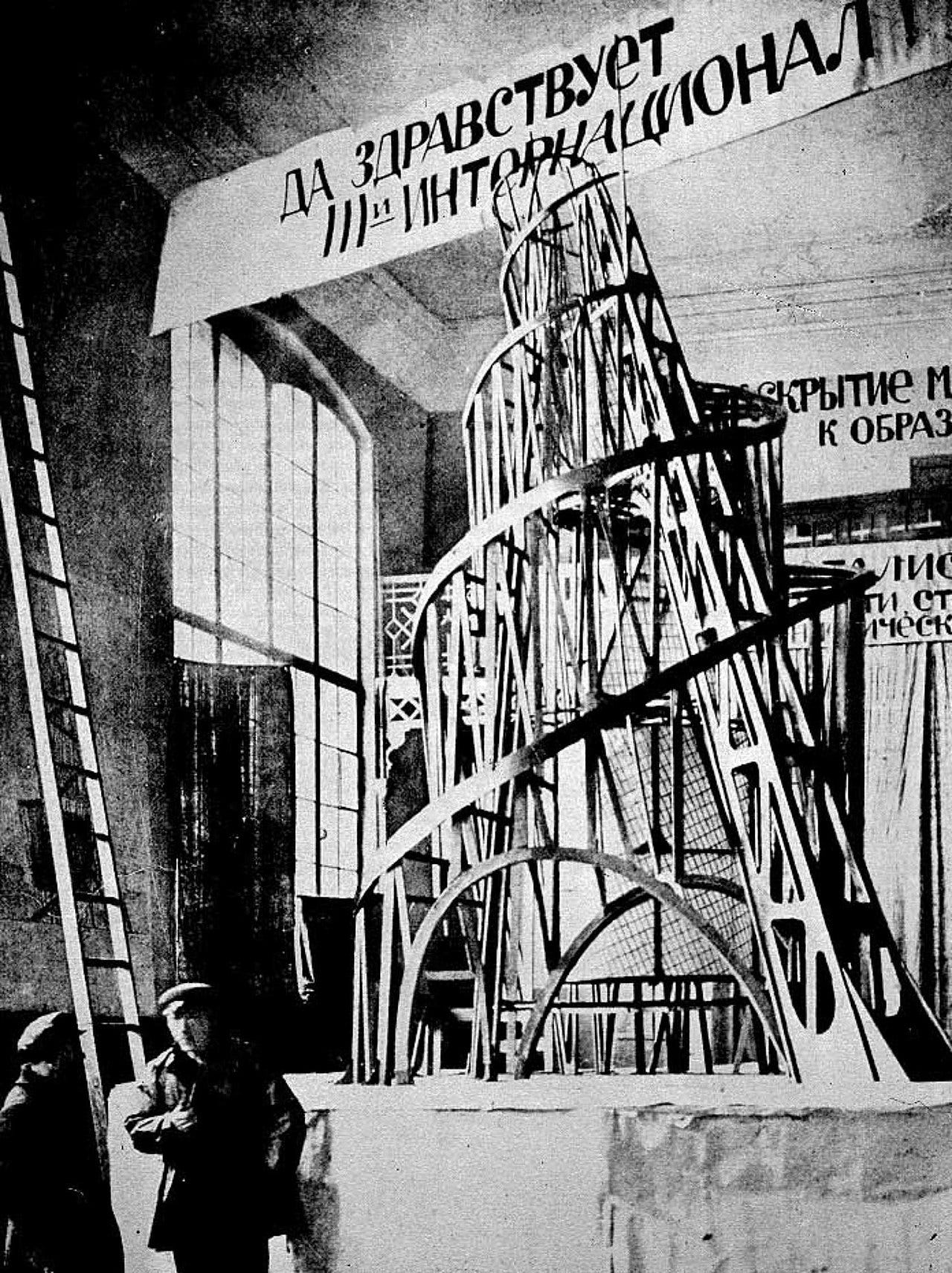

Do you remember the Monument to the Third International? Vladimir Tatlin’s 1920 design for a 400-metre steel structure that would straddle the river Neva in Petrograd, and was never built. It is completely different from Untitled [No one ever shows you off], except that it was also designed to rotate. More precisely, the three enormous cylindrical stories within it were, their revolutions to last a year, a month and a day respectively. The fridge, on the other hand, turns in the manner of a 20th century department-store display of a shiny product, as if to arouse a customer’s desire for it.

(A model of Tatlin’s tower)

But although the readymade on a plinth is more suggestive of a shoppers’ paradise than a socialist utopia, more post-minimal than constructivist (though there’s an echo of that in the layout of the stickers), it is nonetheless a monument to a story, not of political revolution or the motion of the planet through the heavens, but of an intimate alignment of two people. This relationship is articulated through an economy of things acting as metonyms for it – a relationship, I’m guessing, far more important than any sky-grasping tower could be.

Rear View runs at Biblioteka, Peckham, from 12 - 23 April.