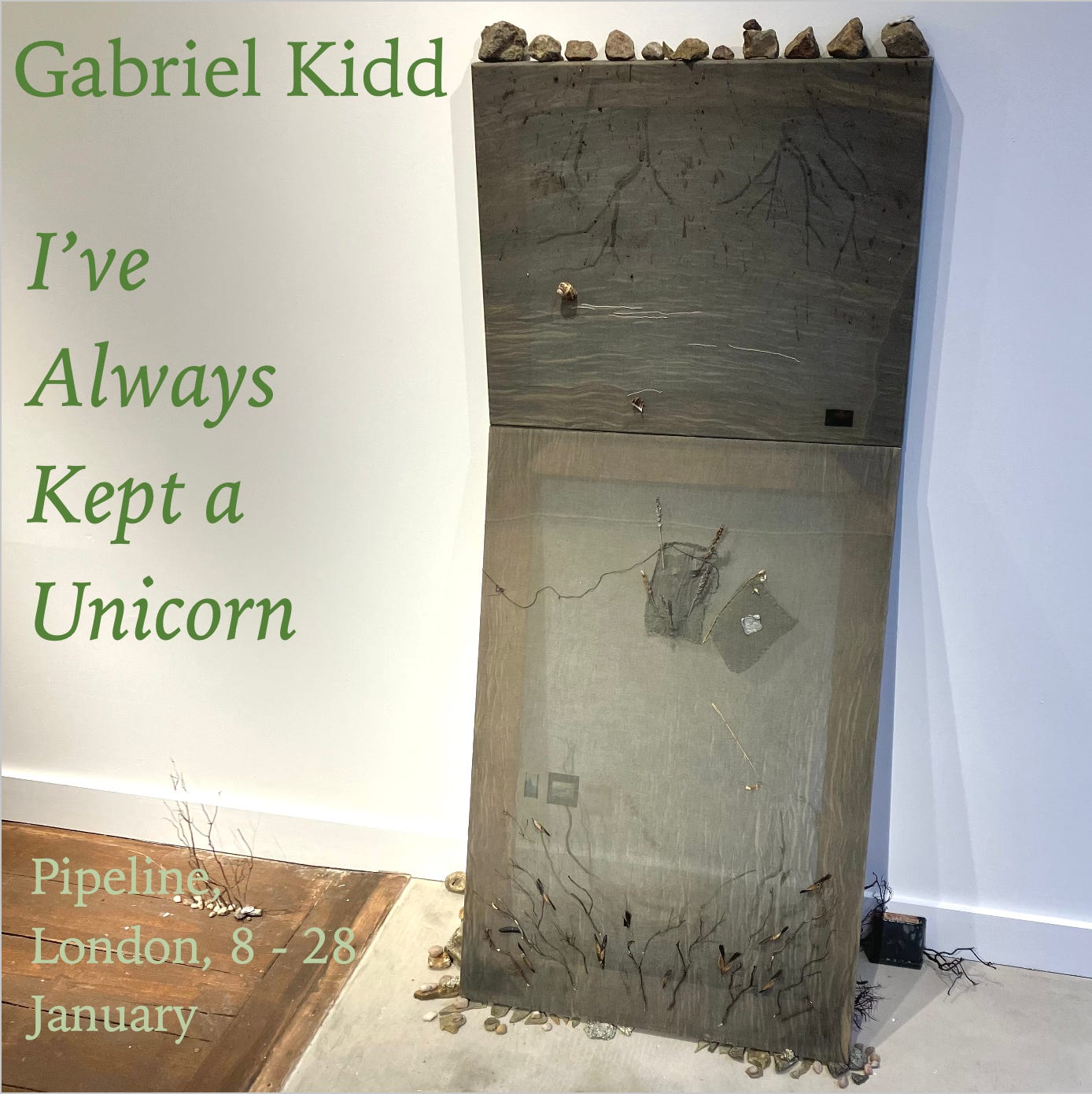

Gabriel Kidd, I've Always Kept a Unicorn

Pipeline, London 8 - 28 January

Once upon a time, a picture surface was considered analogous to a window that looked onto another world. Then, later, people started to think of it more literally as an opaque plane that had paint applied to it. This so frustrated Lucio Fontana that he slashed a canvas open, proving beyond doubt its three dimensionality. In Gabriel Kidd’s solo show I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn, the surface is treated differently still, blurred to the extent that it loses its solidity, becoming unfixed and ethereal, its boundaries in question.

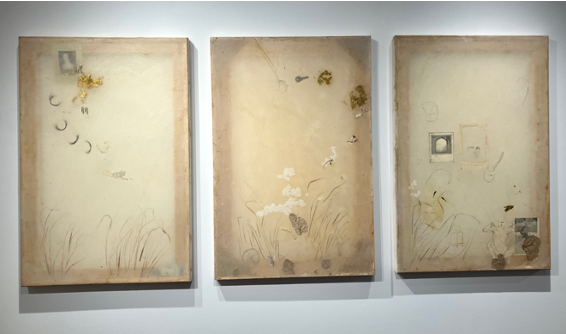

In the triptych Ald Hyll, for example, objects seem to drift across both sides of the taught cotton support. Blades of grass are sealed within the applied layer of latex, while leaves are stuck on top of it. These organic materials drift through as if carried by the wind. The translucency of the surface adds to this porous effect – you can see the wooden stretcher that holds everything up – and the sporadic unfinished pencil drawings and small photographs contribute to the sense of ephemerality produced by these transient-seeming things, somewhere on, or in, or behind or around the pictorial surface.

Ald Hyll

In Red hillsides, a branch of heather nestles behind the red-stained cotton. On the front, at top left, two pockets are sewn on, containing what looks like a circular piece of metal and a small stone. Unlike the grass in Ald Hyll; these seem to have been purposefully kept safe. Together, the works are like a country walk in which you might occasionally stop to pick something up, while the rest of the world passes gently beyond. On this walk, however, the countryside has undergone the nebulous but unmistakeable process of queering.

Queering discovers a latent sexuality in things, while emphasising the permeability of the usual categorical boundaries, especially the ones between sexual and gender identities. Kidd’s porous surfaces are the first of many aspects of the work that escape categorisation, while frequently alluding – in Ald Hyll via the latex – in some way or another to sex. Less ambiguously, in the small pencil drawing A man is watched, is desired and desires, an aroused, reclining male figure is loomed over by a huge skyward phallus.

Beyond the obvious eroticism, the drawing does a considerable amount of boundary-shifting. The tumescent human form is identified with plants and fungi like the cap of a mushroom or the trunk of a tree, and a leafy branch springs up from the urethra. Queer sexuality is elided with the life processes visible on this countryside amble, a connection that is further emphasised by the somewhat blunt double-entendres of the titles: The angels are cumming, Bone me on the hillside (the latter work contains a piece of bone).

In the gallery, little lines of stones are balanced on some of the canvases and along the skirting board of the gallery, bundles of plant matter are tucked into corners, blades of grass poke up through the floorboards, and there is a small mound of earth on the floor, as if to further erode the boundaries between art and exhibition space. But this detritus belongs properly to neither, occupying an unsatisfying nether ground. It is unnecessary because the boundaries of works of art, especially Kidd’s are already unfixed. Art straddles geographically distant places; its audiences bring to it an infinity of their own ideas. Kidd’s gentle, beguiling objects do their work well enough already.