Though they’re clearly in the room, many of the paintings at Guts Gallery’s latest exhibition give the odd sense that they are in fact not there, but somewhere else. (It’s My Party) I Can Cry If I Want To shows the work of ten or so artists, mostly painters, some photographers, and raises questions about the relationship between painting and the infinitely reproducible digital image. One apt photograph in the show sums up much of the painting. In Female Artist Self-Portrait 02062021 by Victoria Cantons and Xu Yang, a woman is seated or standing in front of a reversed canvas, palette and paintbrush in hand, facing towards us. Here, the act of painting is literally performed for the camera.

Victoria Cantons and Xu Yang, Female Artist Self-Portrait 02062021, 2021

Painter Olivia Sterling exhibits a large unframed canvas with a fridge-eye view of Nigella Lawson reaching for a slice of cake. The acrylic paint is thin and flat, without variation in surface texture. The large area of red, representing Lawson’s top, is monotonous except for small areas of shadow at some of the edges. The vertical line demarcating her breasts is a thin, scrappy tail. Don’t Be Timid (Nigella’s Midnight Snack) seems to have been painted with a maximum of expediency, concerned with applying an image to the canvas, but not with fusing image and object into a sympathetic relationship with each other. Thus divorced, the image has few obligations to the thing it’s painted on; all the better for its circulation online as a digital file.

Olivia Sterling, Don’t Be Timid (Nigella’s Midnight Snack), 2022

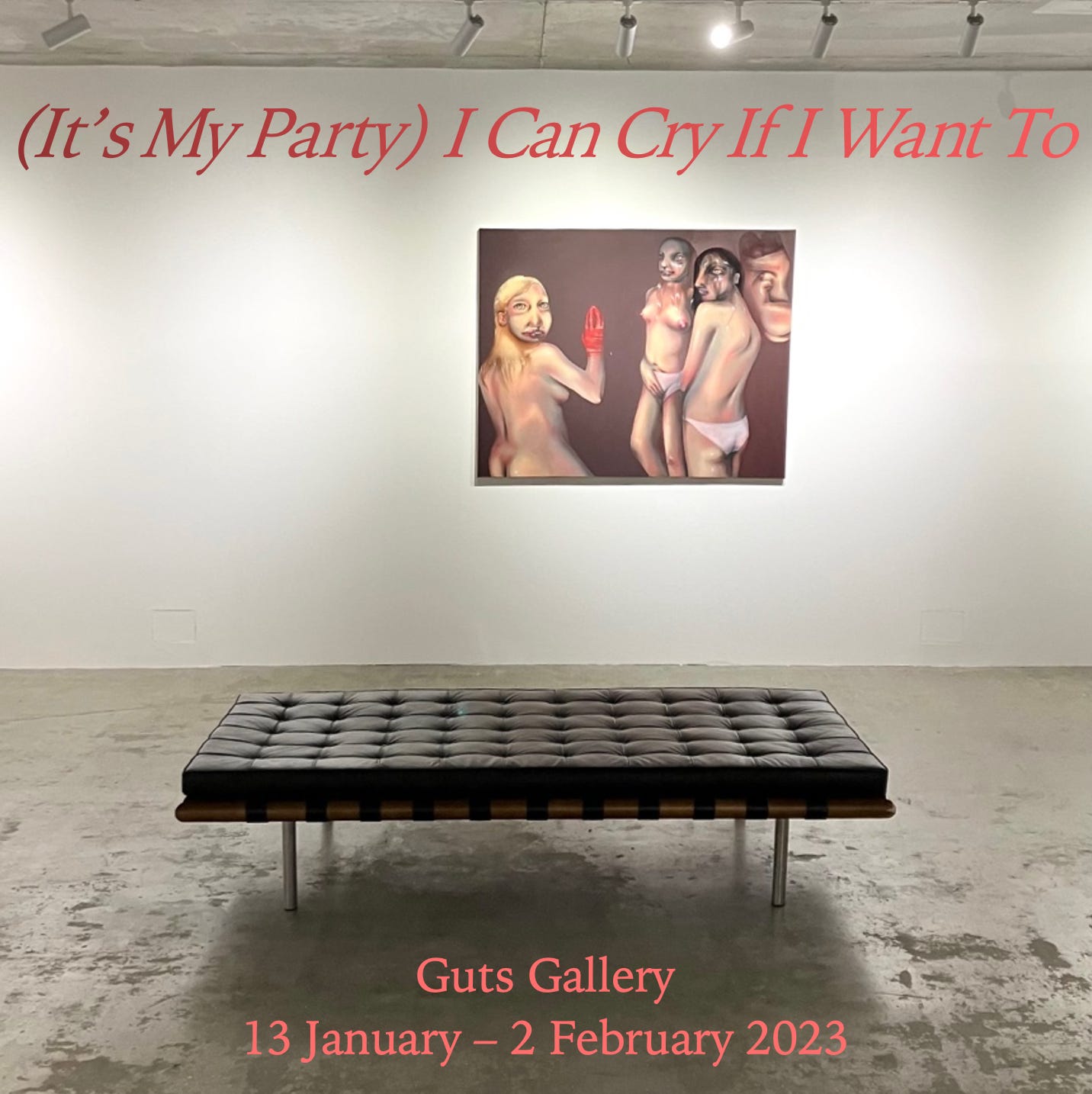

With cyberspace seemingly in mind, the painting feels distracted, present but not present, like someone looking at their phone. Elsa Rouy’s Bloodflowers also invites comparison between painting and digital images. The three principal figures and the smaller couple at top right are painted as if by digital collage. Each human figure is crisply delimited by the heavy, opaque, purplish background. Contrastingly, thin washes of colour produce the modulations of their flesh. Small flecks of white pick out highlights which give the figures a glossy appearance, an effect that is enhanced by the camera.

Elsa Rouy, Bloodflowers, 2022

In person, Bloodflowers feels schematic, a series of painting techniques applied side by side, figures dragged and dropped onto a neutral background without being integrated with each other. On camera, the image comes together, the screen acting like a thick layer of varnish. It feels less like an original, unique object, more a master copy of an infinite chain of reproductions. In theory, this could be a radical gesture. There is an argument to be made for rejecting the unique existence of the work of art, banishing forever the cult-like aura of the original.

It just seems unlikely that this revolution will be achieved through the medium of easel painting. I don’t think that’s what these artists are going for. Instead, the preoccupation with digital reproduction is a response to the importance of social media to the current art market, at the cost of tingeing the flesh-and-blood gallery visit with disappointment. One painter who resists the encroach of the digital on their work is Vilte Fuller, whose frames are emphatically handmade, reasserting their materiality. Will this be enough to preserve the aura of painting? Should it be preserved?