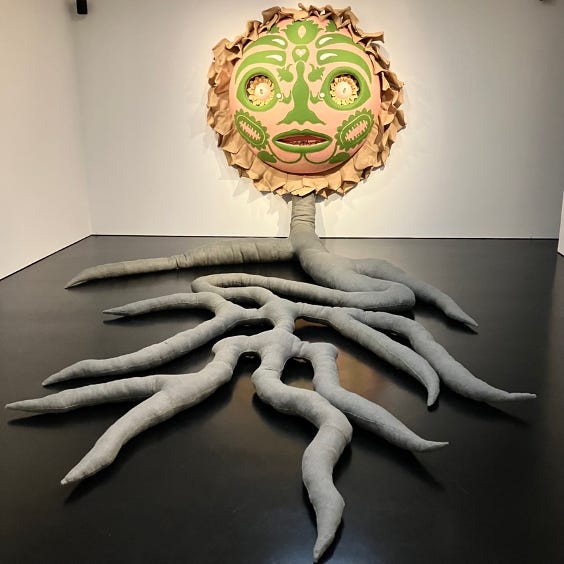

Jonathan Baldock has assembled a garden of oversized flowers that line the walls, their stuffed canvas roots trailing to the dark floor of Stephen Friedman’s street-facing gallery. In the back room the show reaches a kind of climax, revealing a supersize plant, its wide-eyed, Spirited Away face resembling some benevolent nature spirit who loves to receive visitors. However, visitors might not stay too long once they come to the awkward realisation that the nature spirit is dead.

Yanking a plant from the ground by the roots is a sure way to kill it. This is what seems to have happened to Baldock’s flowers, which surprise with their lack of vitality. The deathly casts of human faces that emerge from amidst ceramic stigma and stamens register little more than the forbearance of someone having her face cast in plaster.

The oddly noticeable cleanliness of the sculptures and their suspension in the sterile exhibition space occlude the presence of life. Could any garden possibly be this clean? These unfortunate things might once have lived but they clearly no longer enjoy that state. It’s a taxidermised garden.

The plants have the complacency of a corpse, as if viewers ought simply to be glad at their having lived, or satisfied with how neat they are, with the repetitive juxtapositions of vegetal and human forms, the blithe expressions of the faces and the bright and happy colours, which seem intended to delight in the way a child’s picture book delights a child.

But when presented as art to a roomful of adults who, cheerful as we are, need more than simply infant stimulation to enliven our aesthetic, intellectual and/or spiritual faculties, the sculptures leave a feeling of disappointment. This is all the keener at an exhibition that, following Baldock’s first solo show at Stephen Friedman in 2019, promised to deliver. In fact, it is somewhat offensive to assume that a child would be seduced by its moderate level of wackiness and the mere presence of bright colours, so I apologise for that. Children can be very discerning critics.

A few streets away Yayoi Kusama has window-dressed an outlet of Louis Vuitton. Her spotty surrealism is a perfect accompaniment to the shopping habits of London’s super-rich. It demands nothing from its audiences, hastening instead to flatter and amuse while massaging the cash from their pores like the suckers of an octopus or the tendrils of a venal vegetable.

Baldock’s exhibition puts in a strong application for a similar role. Surrealism can work when it produces startling and challenging contrasts, not this harmless, inoffensive, frictionless mode of fantasy, trying hard to please but having little to say.