Let's start a family

Amedeo Polazzo's exhibition 'Die Strudlhofstiege' at Herald Street, London is a picture of life

It’s happening. People are settling down. And not just people, but friends of mine. And not just settling down, but settling down and having children.

Having attained the embarrassing age of thirty, the notion of having children, until now serenely irrelevant, has for me taken on new dimensions. It now feels, perhaps selfishly, like the guarantee of a fulfilled life. Get it done, and happiness and purpose will be secured. Fail, and I grow old and die unloved and alone.

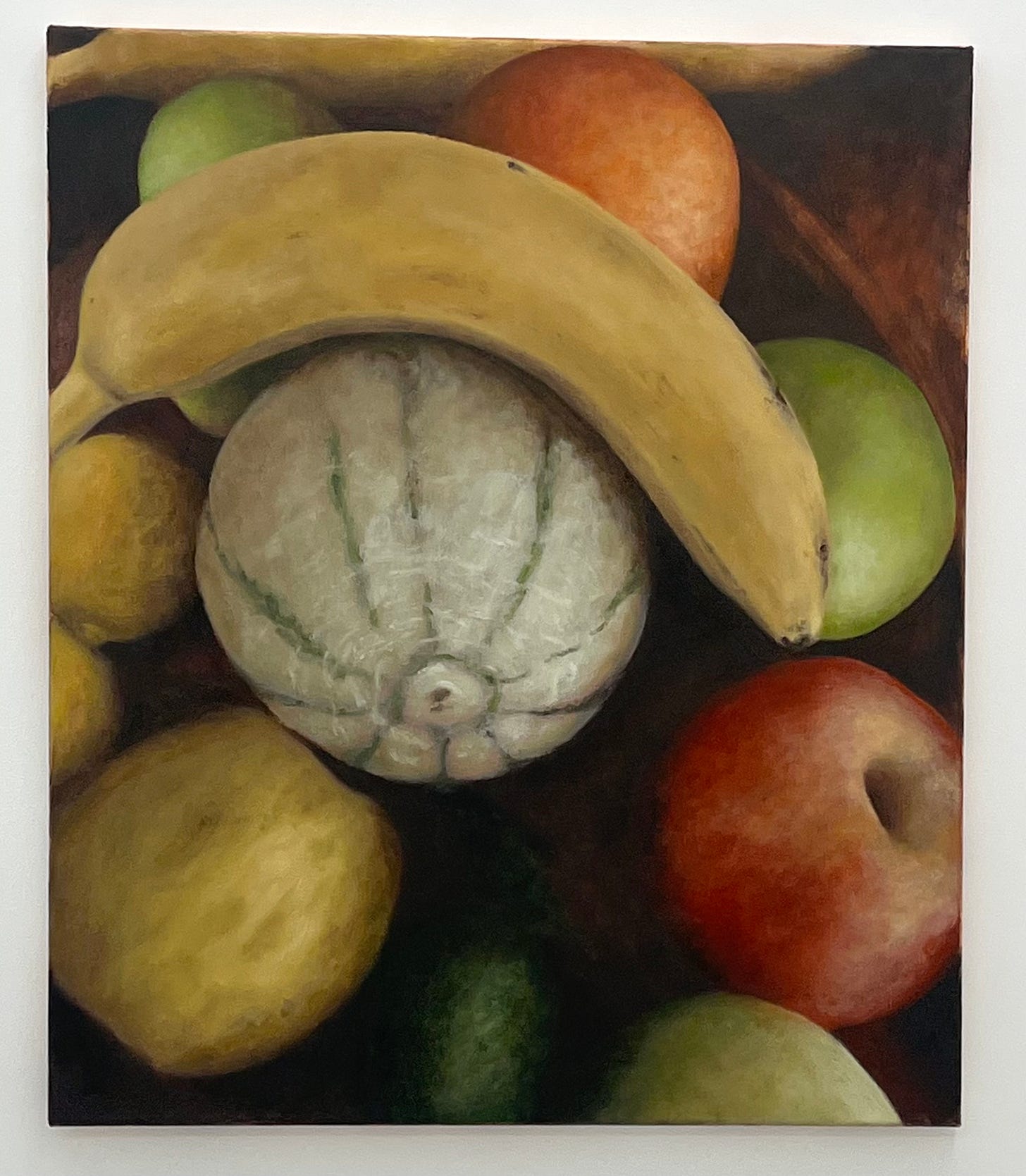

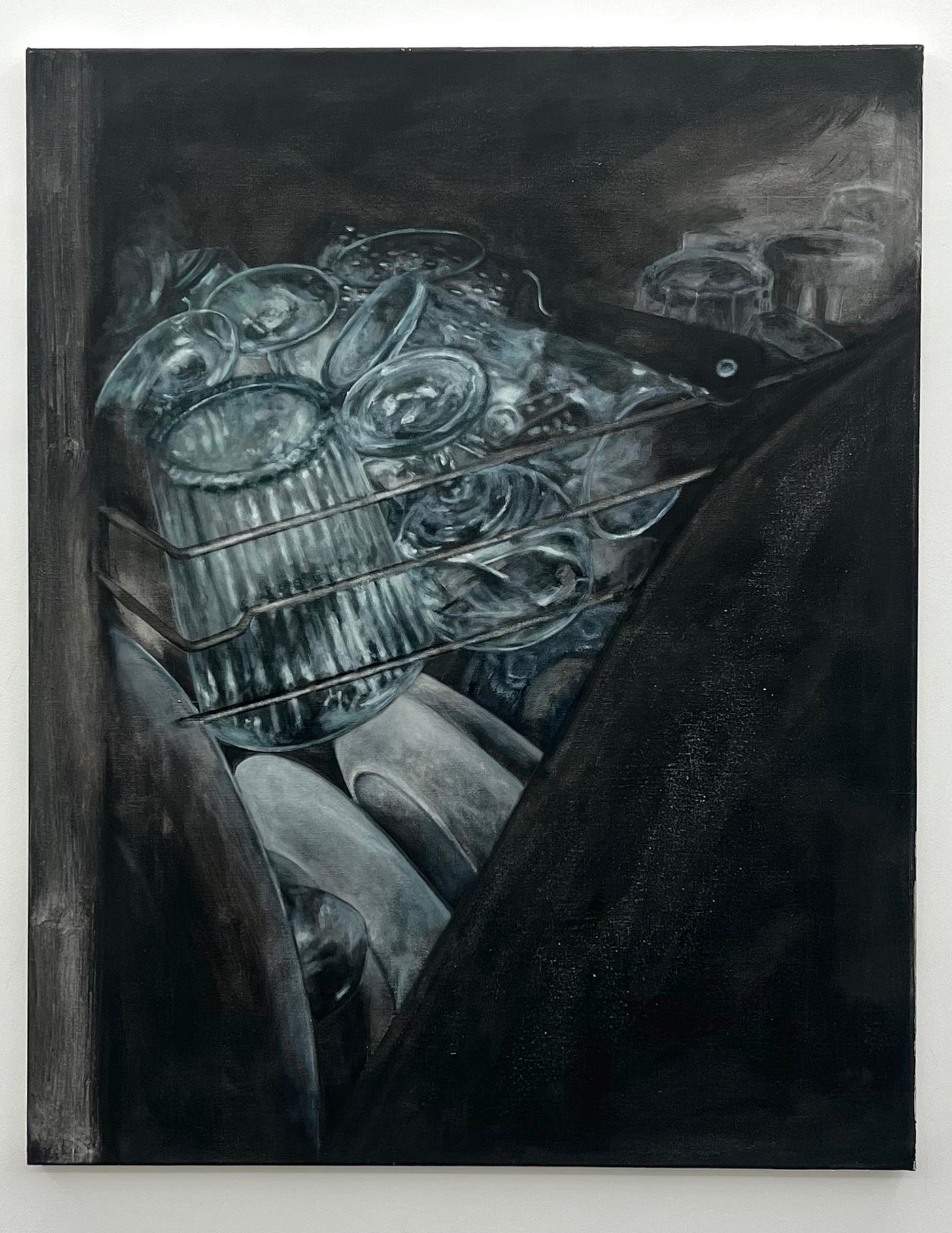

Amedeo Polazzo is a made man. The exhibition ‘Die Strudlhofstiege’ is a chapel to the domestic happiness that he seems to have found. Soft, still paintings show ordinary objects as if seen with renewed vision: a full, steaming coffee pot; the dishwasher; a leaf drifting along a river; the family dog, painted on the wall of the gallery, waiting for someone to chuck the tennis ball; lots of fruit and vegetables, so patently an allusion to the generative organs and yet so innocent you can show them to anyone. In one corner of the gallery, a small painting of the artist’s partner, brown eyes gazing shyly from her bed, is surrounded by a pink wash. It is highly conventional; it is hard not to envy him this life.

The artist had a couple of weeks to prepare the space, hence all the painting on the walls, including children’s playroom-style yellow flowers over the fireplace opposite the entrance. At the back of the gallery, Polazzo has continued the lines between the floor tiles to produce, if you look from the right position, the illusion of an infinitely receding space beyond the wall. At the point towards which the perspectival lines converge is a small painting of some flowers. On a petal sits the focus of the chapel: a tiny baby.

Single-point perspective was never a purely formal device. When it was developed during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, artists would think carefully about the meanings it encoded in their paintings. Above all it was useful for pictures of the Annunciation, the moment when Mary conceives Jesus. That is, the representation of infinite space (single-point perspective) through material means (panel painting or fresco) was developed to depict the moment when the infinity of God became material and measurable in Jesus. Get it?

It is therefore apt that the perspectival scheme in ‘Die Strudlhofstiege’ is oriented around the child. In one’s child, all that amorphous searching for meaning suddenly takes on the form of a real, tiny human being. Or so I’m told. Unfortunately, this also confirms my catastrophic fears that sexual reproduction really is the key to meaning, purpose, joy and all the rest of life’s good things. How can I, and others like me, not suffer under the persuasiveness of this case?

Obviously this is a narrow perspective on life. Something else might fill the meaningful gap. Maybe the universal baby, the Christ Child himself. Or maybe you can do away with perspective altogether and paint amorphous blobs down your bedroom wall until you are recognised for your contribution, although probably not till after you’re dead. It’s not like we can control these things anyway. But ‘Die Strudlhofstiege’ doesn’t seem like too bad an alignment if you can get it.

‘Die Strudlhofstiege’ runs at Herald Street, WC1, from 13 February to 29 March 2025