Milton Avery was a quintessential artist in the late romantic mould. Although he didn’t get started until his thirties, painting was his vocation. He came from a working-class background and worked nights so that he could devote the days to painting and painting classes, not having gone to art school. Eventually he started to exhibit, and by the time he was fifty he was getting pretty good.

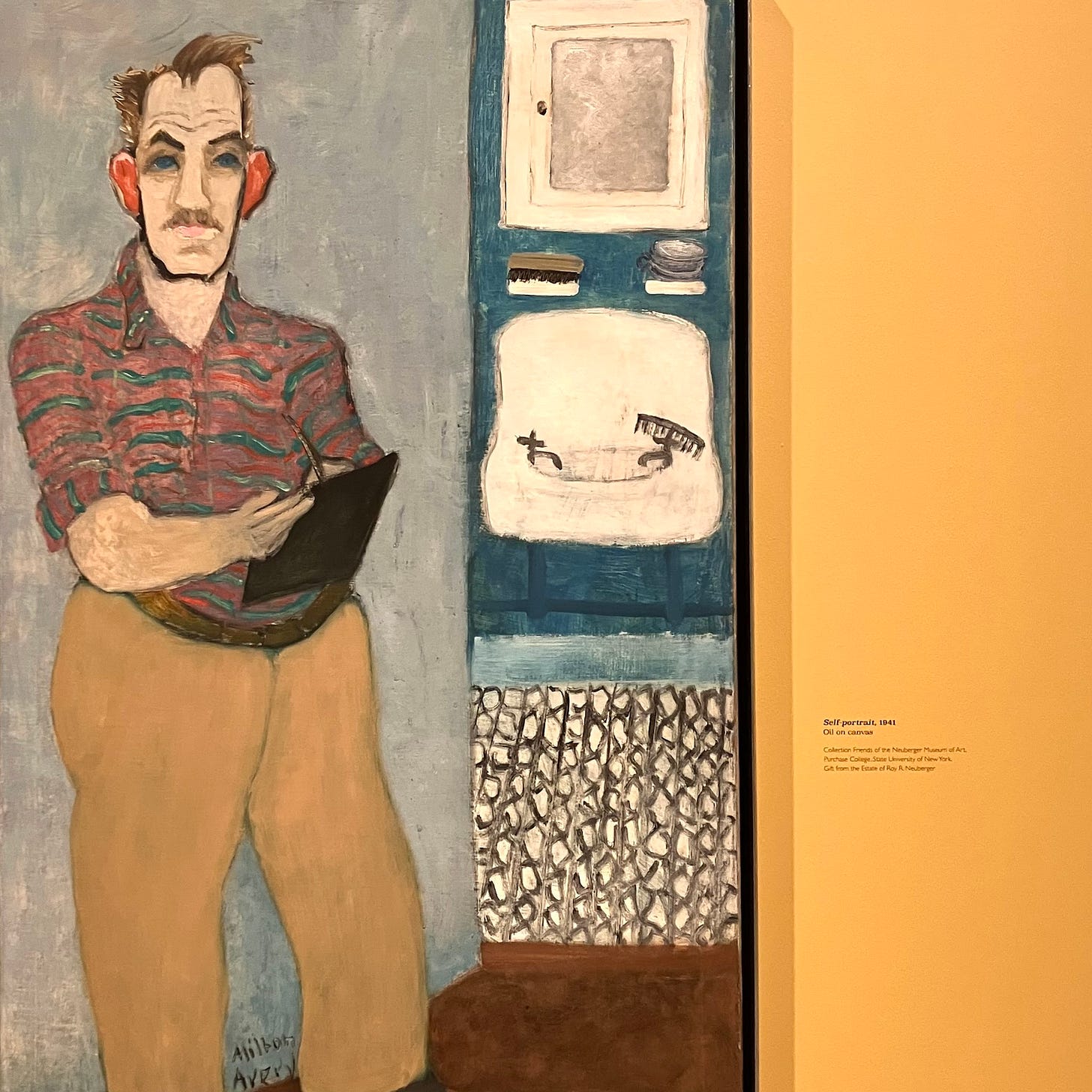

The monographic exhibition format matches the myth around an artist like Avery: the inspired man so committed to his art that he produced a new painting almost every day. A self portrait shows that he had a similar image of himself. He is an impassioned hero in the mould of Beethoven, gazing off into a sublime distance. But there’s someone else in the picture: his wife, Sally Michel Avery, her sidelong smile suggesting that she finds his pretensions faintly amusing.

The show could tell us a bit more about her. She organised soirées at their New York apartment where the likes of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman would congregate, and she probably had to work quite hard at them, given that Milton was a ‘man of few words’ and would mostly sketch. She supported him financially when he wasn’t selling. And she was an artist too, apparently. I wonder what her work looks like.

Milton Avery’s paintings show he is under no illusions about gender roles. In Husband and Wife, a man with a shock of blonde hair sprawls raffishly in an armchair, smoking a pipe, while his wife sits tidily at the edge of a yellow sofa, her arms folded. This sensible woman, like Sally, provides the domestic foundation from which pipe-smoking dreamers like Avery can project their inspiration onto their canvases and into the world.

Without Sally, Avery is unlikely to have developed the way he did. He produced a lot of rubbish, some of which is in this show (the gift shop predictably sells postcards only of the worst ones). But he managed to refine his technique while maintaining the same trajectory throughout his career, sticking to his guns. Over time, he develops his control over the rough paint handling of the earlier paintings, locking it more firmly into place. His palette brightens, the paints thin and the canvases get bigger and feel fresher.

Avery’s great accomplishments – for me, Blue Trees, The Auction and, at the end, the near-abstract Boathouse by the Sea – are a testament to his hard work and pertinacity. But they are also the work of Sally Michel Avery, whose presence you can feel throughout the work. Monographic exhibitions persist because we’ve learnt that you cannot separate a modern artist’s life from their art: the two are bound together in a tight fusion of necessity and mythology. But rather than canonise yet another solitary genius, we’d do better to remember that great art is rarely made alone, and that Avery worked in a team.