Is it perverse, at an exhibition dedicated to recent art school graduates, to most admire the artist whose work least shows the signs of tuition? New Contemporaries gives the newest generation of artists the opportunity, often their first, to exhibit in a major show. It’s a chance to get noticed, meet peers, find a collector, launch a career; at the very least it’s fodder for the CV. Clearly, this is a good thing. But since the show takes a group of artists who have just come out of university education, university education looms large, though its teaching methods are never discussed. In such a show, an artist who has come up a different way is likely to stand out.

The selection criteria determine the outcome: these artists are, for the most part, the students who have excelled in the academy, who are the most adept at the techniques and protocols that British art schools teach in preparation for a career as an artist. Despite plenty of good work, this mode of display hints at a kind of 21st century academicism; one that takes place on a conceptual rather than practical level, but which nonetheless produces work that fits comfortably within the expectations that audiences bring to their encounters with contemporary art.

Though it’s nobody’s fault, this mode of institutional approval feels antithetical to contemporary art’s potential to disrupt and subvert. These motives are, of course, difficult for any institution to teach, and have spawned an entire class of curators adept at arranging objects to maximise their effectiveness, which is necessarily muted in a large group show. And the show, rightly enough, seeks to represent the breadth of approaches and ideas of recent graduates without favouring one over another. But holding such an exhibition coherently together is a near-impossible task, and the disparate ideas tend to sap rather than enhance the energy in the galleries.

More important, New Contemporaries implies that the years following graduation from art school are a time in which an artist can liberate their work beyond the training these institutions offer. This could be part of a much-needed corrective to the eagerness with which young artists are skimmed off MFA programmes to be milked dry by a gallery hungry for the next big thing (and profit). Artists, though they be talented, may also need time to mature.

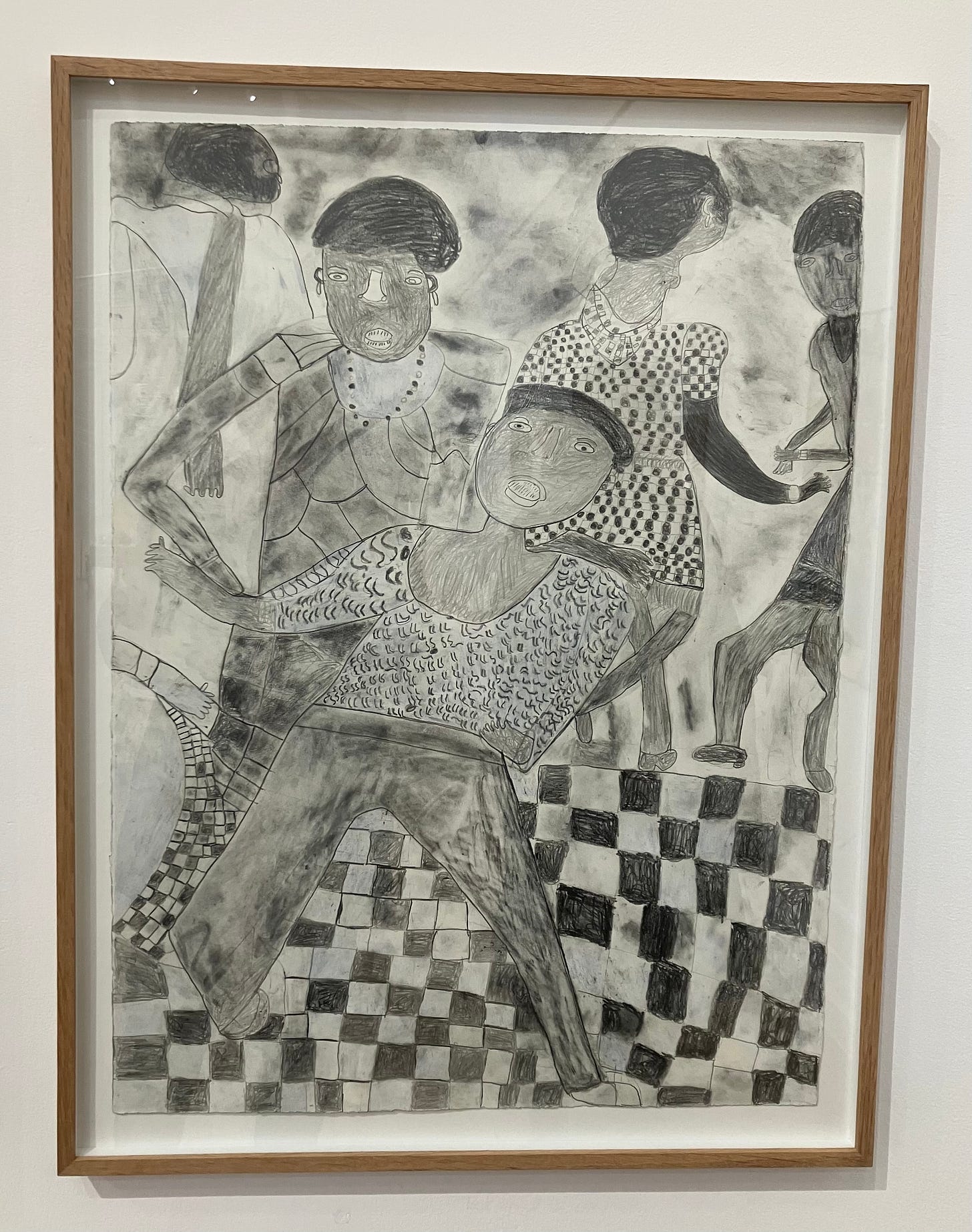

The artist, by the way, whose work seems the least taught – but is the most memorable – is Dawn Wilson, whose charcoal and graphite drawings represent figures, many of whom are dancing, with back-to-basics directness. Their style, with heavy outlines, rough, sketchy shading and chequered floors that don’t quite line up, is difficult for anyone over the age of about ten to pull off, yet the figures also have a graceful sense of weight and movement that speaks to experience rather than naivety. The drawings make a lasting impression with their simple accomplishment. Wilson was born in the 1960s and has recently studied art at a Peckham charity for adults with learning difficulties. The academy is not the only place to learn art’s secret.

Dawn Wilson, Dancing in the Club - Bamako, 2019