Peter Doig

The Courtauld 10 February - 29 May 2023

The word ‘superficial’ literally means ‘on the surface’, but it is more often used loosely to mean ‘insincere’ or ‘lacking substance’. Much the same is true of contemporary painting. While some artists rigorously exploit the potential of the painted surface, many more employ superficiality only in its colloquial sense, repeating it like a mantra while knocking out canvas after canvas of Peter Doig pastiche. Of course, that’s not necessarily Peter Doig’s fault. The first challenge at the Courtauld show, therefore, is to forget the imitators and find out which sense of this word takes priority with him.

Sometimes, it’s the second sense. Music Shop is a picture of a freewheeling musician in front of the seaside shop. Sure, there are devices like paintings-within-the-painting or uncertainty about whether we’re inside or outside, but they don’t make up for the fact that the central figure is a trope, exhausted at a glance. However, this is one of very few lows in a group of paintings that, for the most part, realise a genuinely profound superficiality.

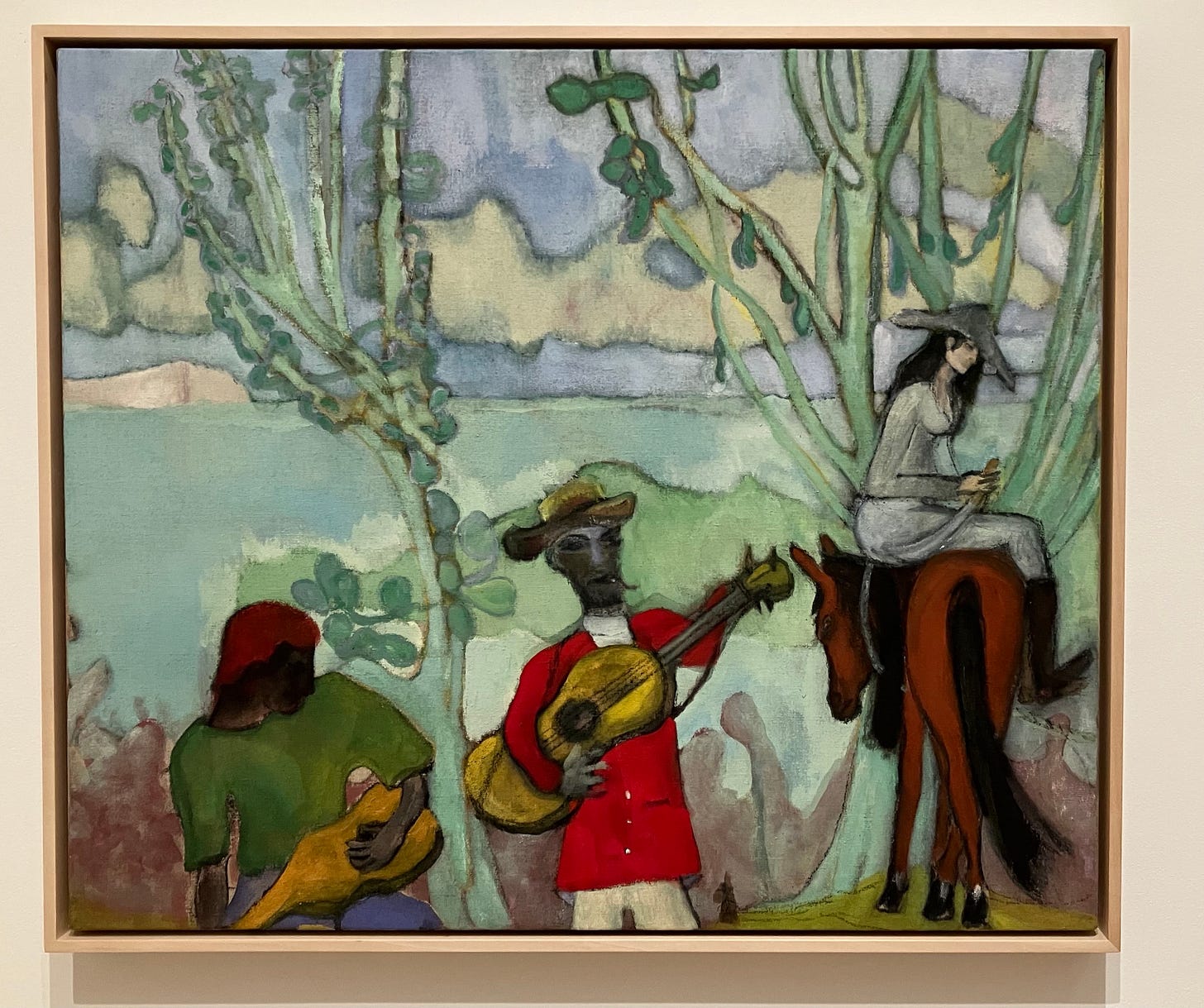

For example, in Music (2 Trees), the two guitar-playing figures have their legs sliced off by the bottom of the canvas, and look as if they have just popped up in front of the luminous trees. The figure on horseback mediates between them and the recession of the background, producing an oscillation that takes the painting’s illusory depth seriously, while acknowledging its material flatness. Though awkward, the composition just manages to hold together, the more excitingly for it.

Music (2 Trees)

Alice at Boscoe’s represents a child straight out of an Enid Blyton illustration lounging in a hammock in a garden of garish orange and green. Much of the child’s body comprises canvas left unpainted and unprimed. This inverts the usual emphasis given to a foreground human figure. Figuratively speaking, the child is the closest thing to us, but tonally she recedes into the background, while materially she is identical with the canvas support on which the rest of the paint is applied. Superficial, yes – but a wise superficiality in which multiple levels of association collide.

Alice at Boscoe’s

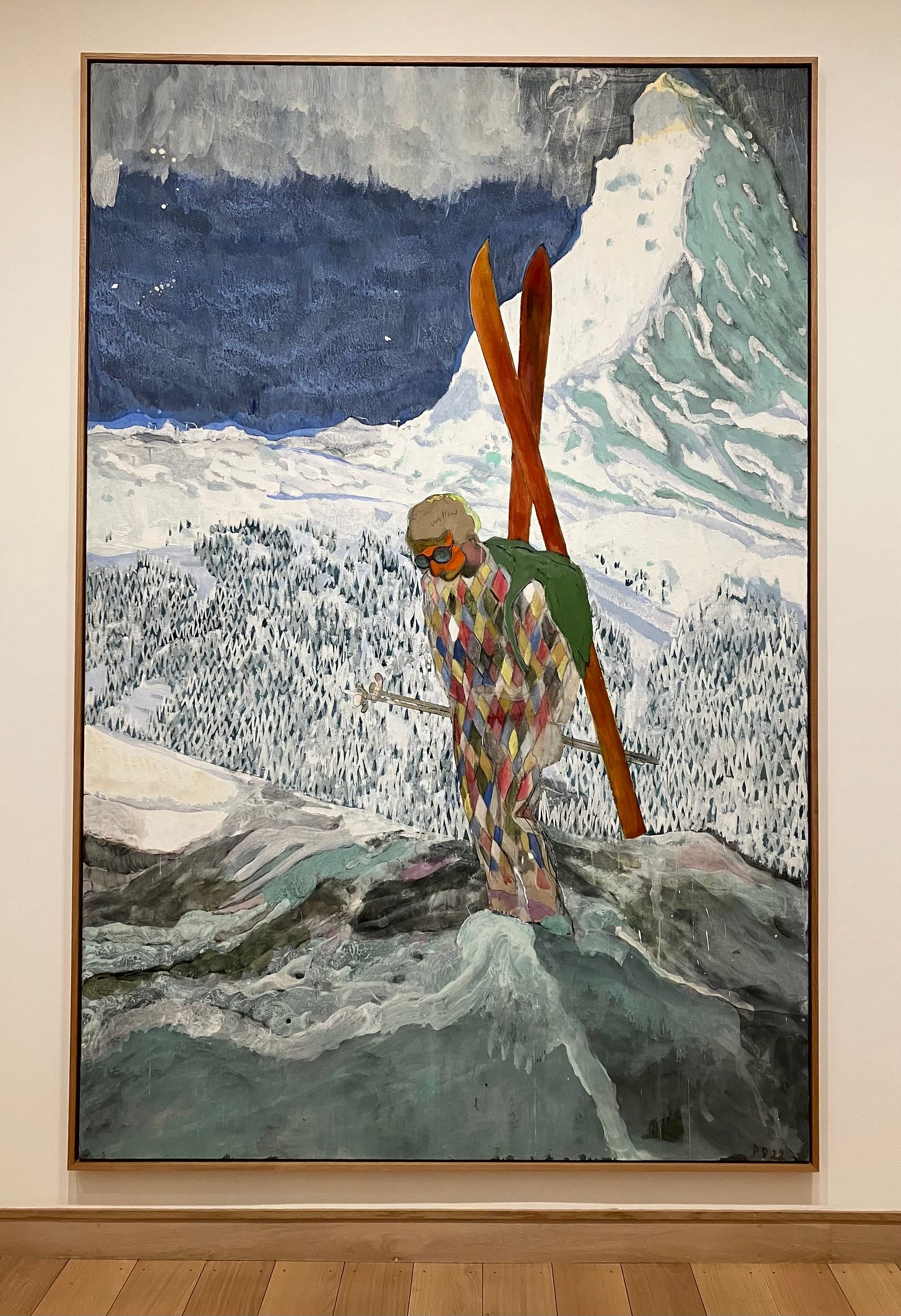

The best is saved for the second room of this confident and concise exhibition. Alpinist is all about triangles and diamonds. There is a parallel between the pattern of the harlequin’s ski suit, the negative space between the crossed skis and Doig’s shorthand way of representing the snowy trees, the obviousness of which does nothing to diminish the pleasure of seeing them side by side. The simple but effective interaction between geometry and figuration culminates in the breathtaking mountain, responding to all the little shapes in their own language: as a big triangle.

Alpinist

Doig’s superficiality runs deep, and watching this paradox play out in the flesh is one of the great pleasures of his, or any, painting. But didn’t all that talk about flatness die out with modernism? Judging by this show, no. Doig is obsessed with the potential of the surface. He has been able to apply lessons from an approach to painting that once favoured abstraction to his own, figurative ends. That is a sign of greatness.

This is an excellent review which really got to some of the things that I find interesting about Doig's

work, as well as insightfully discussing contemporary painting in general. It made me want to look closer. Excellent.