Playing God?

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, 'The Rebirthing Room', Studio Voltaire 31 January - 28 April 2024

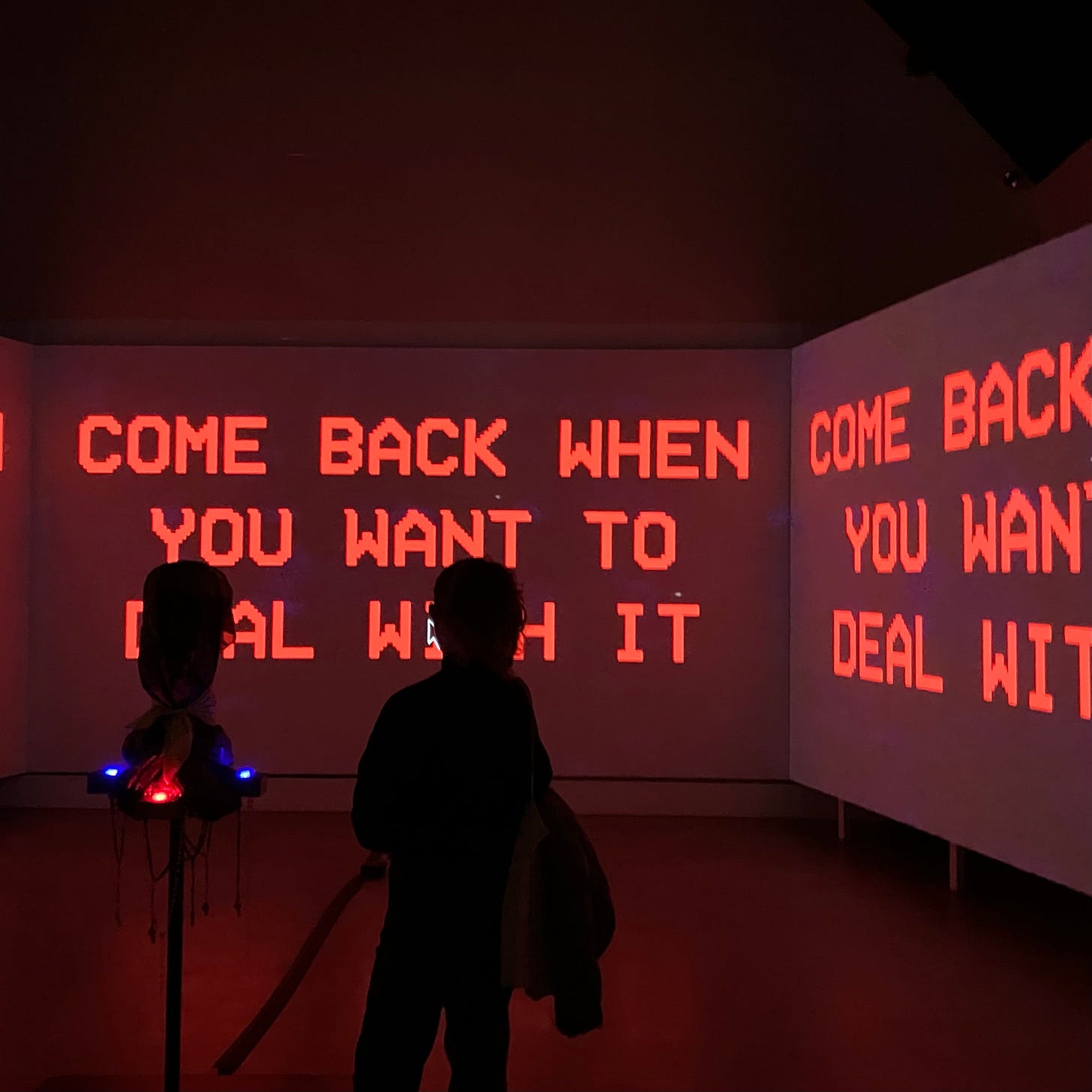

After some preamble and an instructional video, the visitor to Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s ‘The Rebirthing Room’ at Studio Voltaire passes through a dark room filled with several towering columns to which are attached small religious objects like a Black Madonna and Child icon, until they reach the ‘anchor’ – a free-standing video game controller in a clearing, surrounded by three large screens. The aim of the game is for you to be ‘born again’.

In keeping with the cathedral-like installation and its Christian iconography and language, the game employs an evangelisation tactic similar to the public confession that goes on in charismatic churches. A menu screen invites you to select which of your problems you’d like to overcome: anxiety, low self-esteem, fear of failure, intolerance, addiction or self-doubt. Everyone waiting for their turn at the anchor watches you make your choice. Then the game manifests your problem as a series of demons: you have to shoot them down. I chose fear of failure, and before the game began, the screen’s harsh, all-caps text told me to admit what or whom I’d failed out loud to the room.

(Since we’re in confessional mode . . .) I found myself transported to a time when I really was in a large charismatic church and the pastor, in a gentler yet insistent, yearning voice, told the congregation to stand if they wished to accept Christ into their lives. He said to do it quickly and to do it now. Out of exquisite embarrassment I kept my eyes glued shut, so I can’t tell you how many others rose . . .

On reflection, I think that the pastor’s tactic was the manipulation of an inner longing by a potent grip of urgency, shame and expectation. I think that Brathwaite-Shirley’s difficult, confrontational game attempts to grapple the player into a similar hold. Berating its players, demanding confession from them – even when my (very skilful) friend beat the game, it warned them that they were always at risk of succumbing (sinning) again – seems more likely to produce a performative and temporary compliance than a genuine rebirth.

Of course, no gallery video game was ever going to sort out your life for you. Nonetheless, it is still worth maintaining considerable critical distance from the kind of social pressure applied by ‘The Rebirthing Room’. With these tactics, it is not clear where our own will ends and someone else’s overtakes it. We should be highly wary of granting anyone that power. For all the force of its authorial voice, for all the immersion and the adrenaline of the game, there is no authority here to which you should submit. Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley is not God. Remembering this, it felt liberating to reject the uncompromising scheme of guilt and shame through which the installation was directing me – and walk away free.