Rose Salane, Basins of Attraction

I took the enormous double rainbow outside to be a good omen . . .

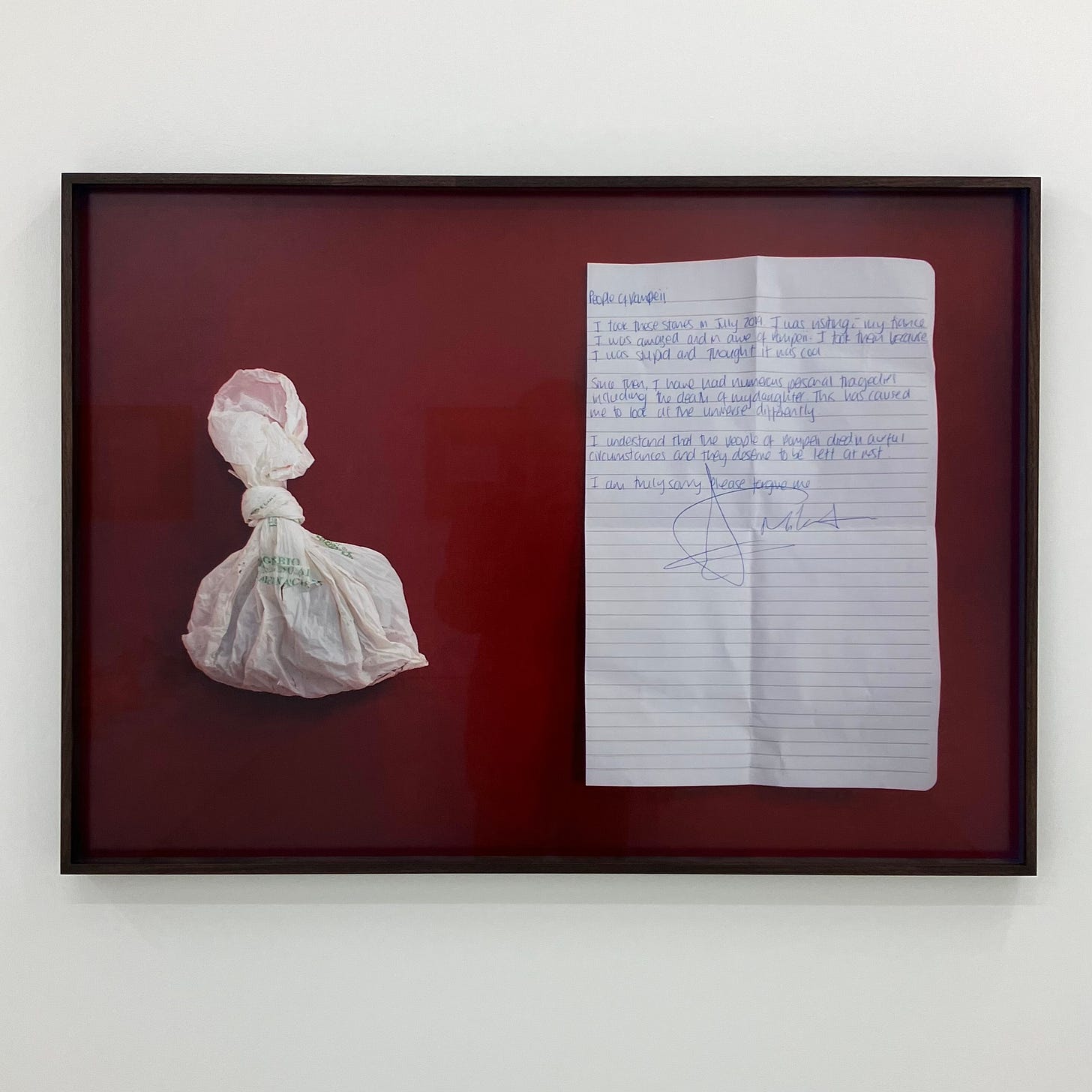

Nothing important – small bags of dust or broken scraps of tile was all they took. Even so, the guilt was too much for these hapless tourists, who posted them back to the site with letters of apology, asking for the detritus to be returned to wherever they’d scooped it off the ground. It’s ironic, because the archaeologists have no idea what to do with what is now effectively litter, so it has accrued in the non-space of the archives, where Rose Salane encountered it, and therein discovered the seed of an exhibition.

Salane’s fourteen photographs of the contents of this archive are a treasure trove of the human conscience. The contrite letters hint at, though never claim, supernatural motivations: ‘[Since I took the stones . . .] I have had numerous personal tragedies including the death of my daughter. This has caused me to look at the universe differently. I understand that the people of Pompeii died in awful circumstances and they deserve to be left at rest. I am truly sorry. Please forgive me.’ There’s another irony here, since if anyone is guilty of disturbing the remains of Pompeii it’s the archaeologists, who have removed more matter from the site than any number of tourists could.

Basins of Attraction asks: how might we make sense of these pangs of guilt? And it proffers the beginnings of an answer, arranging sixty-four identical CCTV cameras bought at auction in New York on a white plinth in the centre of the gallery, surrounded by the photographs on the walls. This puts the self-regulating activity of the tourists into dialogue with themes of security and surveillance.

The juxtaposition is informative about the role of cameras today: surveillance acts on us in non-rational ways that existed at least as far back as the time when Pompeii was a Roman holiday resort. Back then, eyes painted on the walls of an alley would have prevented (some) people from urinating there. Cunning folk were able to extract confessions because people believed they already knew who the guilty party was. Modern surveillance retains a degree of this psychological power: hence the power of dummy cameras to deter rulebreakers.

In the opposite direction, Basins of Attraction is less compelling. The cameras have relatively little to say to the archive photographs. The tourists were moved to return the objects to Pompeii out of conscience and respect for the dead, surely a response of a different order from the neuroses produced by the surveillance state. On the contrary, it is touching that people showed so much care towards these remains. Their example could even prove salutary for other institutions tasked with preserving – or restituting – human remains.

Despite this limitation – could it be called cynicism? – Basins of Attraction is nonetheless a masterstroke of archival research, worth visiting for the photographs alone. The cameras are defunct but the human stories live on vividly. Perhaps that is the point after all.

Basins of Attraction is at Carlos/Ishikawa, Whitechapel, 16 March - 22 April 2023